How do you choose a decking product?

Decks are very popular in Australia, and are often the transition between house and garden. So how do you choose your decking material? Is it price, quality, maintenance or perhaps something more intangible like, how does growing, harvesting and using this product affect the Earth?

If you’re looking for a beautiful, durable decking material for your home, you may be wondering about the difference between traditional hardwoods and bamboo. Both are excellent choices, but they do have some fundamental key differences. So, which one is right for you?

Hardwood or Bamboo: What’s the Difference for Decking?

Bamboo, at this stage, is a high end product comparable to high quality hardwoods and cedars. New technology is enabling the production of plastic derived products that are being marketed as sustainable. They are more expensive but offer less maintenance and a longer warranty, which is a selling point for clients. However I always ask at what cost to the environment?

We often get enquiries from customers who are looking for a price on bamboo decking. It could be because they are looking for a sustainable alternative, or they are price matching against a hardwood and believe bamboo will be cheaper.

Merbau is the most popular tropical timber hardwood material in Australia, largely due to its price. Merbau was originally found from Eastern Africa through Southern India and onwards to Southeast Asia, Oceania and as far as Tahiti. Merbau is slightly dearer than treated pine, but cheaper than Spotted Gum and Jarrah. Merbau timber is also known as Kwila, scrub mahogany and Johnstone River teak, to name just a few. The name varies depending on the geographical region. Merbau is mainly found in Southeast Asia, while Johnstone River teak and scrub mahogany are North Queensland derivations and Kwilia is used throughout Australasia.

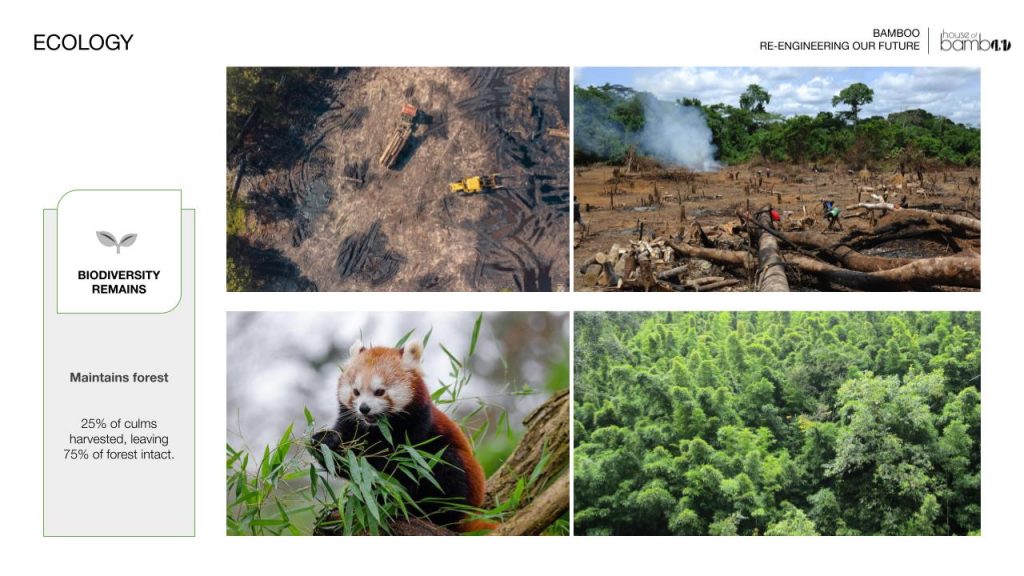

It takes about 40 years for this large hardwood tree to grow to a height of 40m and up to 75-80 years to fully mature. The trunk can be up to 2.5m wide and is branchless for half its height after which it has a spreading canopy. With around 50-10 trees grown per hectare, the commercial stands left are mainly on the islands of New Guinea and Indonesia. The tree to hectare ratio is low and entire ancient forests are often destroyed during logging and the establishment of infrastructure (roads, camps etc) required for logging.

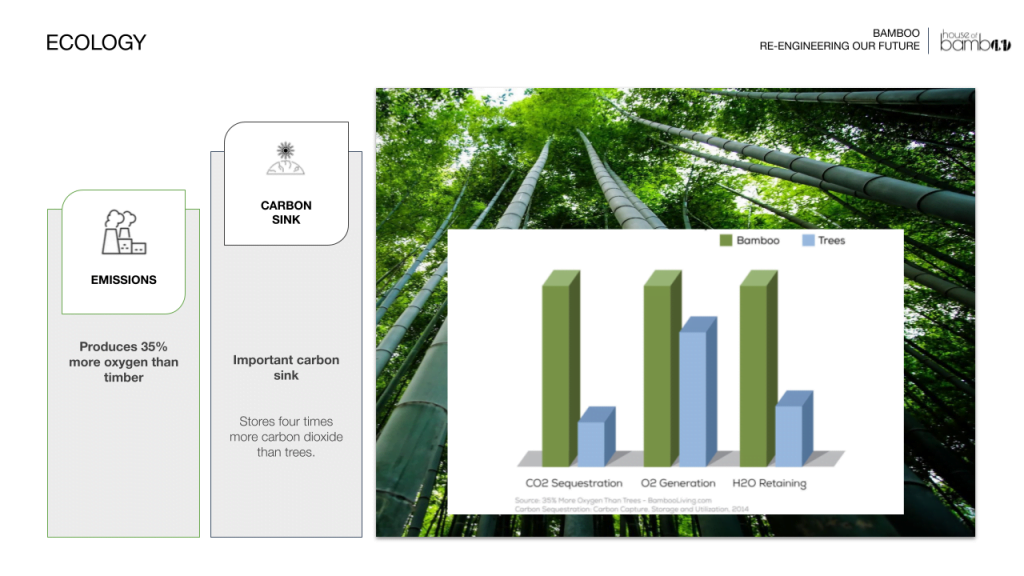

But surely wood is sustainable due to its carbon sequestration and storage? Growing wood in native forests is sustainable because of carbon sequestration and storage in the tree and its rooting system. Living trees can mitigate global warming impact through carbon sequestration. But then you have to harvest and transport the material, and how long does it take to regrow?

Key findings in Greenpeace International’s 2007 report titled “Merbau’s Last Stand” (link https://wayback.archive-it.org/9650/20200516081429/http://p3-raw.greenpeace.org/international/Global/international/planet-2/report/2008/7/merbau-report-2.pdf) included:

- the range of merbau has already been heavily impacted by destructive and illegal logging. Over 60 percent of the original merbau range has been affected by human activity

- At the current rate of officially sanctioned logging, most of the remaining merbau will be gone within the next 35 years (this being the official rotation cycle for logging). This figure does not take into account illegal logging, which exacerbates the rate of destruction and will escalate the speed at which merbau disappears.

- most large international flooring producers include merbau in their product ranges, with the majority of them sourcing the wood from untraceable sources in Indonesia. Few, if any, of the producers are able to credibly prove the full legal origins of their merbau supply

- 76-80% of logging in Indonesia is illegal and the World Bank estimates that 70-80% of logging in PNG is illegal

- Indonesia and PNG have already lost 82% and 60% of their large intact ancient forests

Greenpeace summarised that merbau is hovering on the brink of commercial extinction – and that was in 2007. The IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species 2006 categorised merbau as “facing a high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future” That near future is now.

“The pressure on kwila (in West Papua) has increased over the last years. It is very concerning. The market is growing and the forests can’t stand the pressure.” Bustar Maitar, global head of Greenpeace’s Indonesian forest campaign reported in 2014. Most of the wood is shipped to other Indonesian islands for processing and the compensation to the community is very low. Imagine how another 8 years of logging has impacted the local environment. And this is not a new theory. Greenpeace published a report in 2007 claiming most of the kwila imported into New Zealand from West Papua came from illegal logging. “While the industry has improved, legal logging is only one-third of the way. There are still a lot of problems concerning indigenous rights, protecting the biodiversity and sustainability of the forests” says Grant Rosoman, forest solutions team leader at Greenpeace.

National Geographic reported in January 2020 (link https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/deforestation-in-the-solomon-islands), that logging in the Solomon Island community of Marasa was clearing “kwila and the akwa strung with fruit, then dragging them off the slopes for export, leaving nothing to stop the rains from taking the topsoil.” The villages knew that the forests they relied on for food, water and timber would be destroyed. This is a common thread with the destruction of old growth forests and illegal logging.

So the main problems in harvesting Kwila are sustainability, making sure the local people are treated fairly and damage to the biodiversity of forests.

“High demand for Merbau timber drives unsustainable harvesting practices and illegal logging in tropical forests, causing great biodiversity loss” says Quynh Nghyen from Impactful Ninja.

Merbau trees grow sparsely even in rich forests and with a slow rate of replacement (75-80 years), loggers often end up cutting down many other trees to reach a targeted merbau tree. Once replanted, young trees are at risk of infection and damage which together with the low density and the slow growth rate, result in poor replacement.

A Greenpeace report predicts that most of the remaining merbau will be gone by 2043 at the current official rotation cycle for logging. This does not take into consideration illegal logging, which vastly increases the rate of destruction and will speed the rate at which merbau disappears. For this reason they are on the IUCN Red List of threatened species as they are considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the wild.

The issue with this material, from my perspective, is:

- it is a strong contributor to the destruction of our rainforests

- with the destruction of rainforests there is a direct correlation to the displacement of the biodiversity that exists within its canopy

- sensitive habitats face degradation and destruction through the construction of new roads

- water sources are polluted and require chlorination to at least be made drinkable

- local residents seldom benefit from the destruction of their habitat

So how does Bamboo offer an alternative?

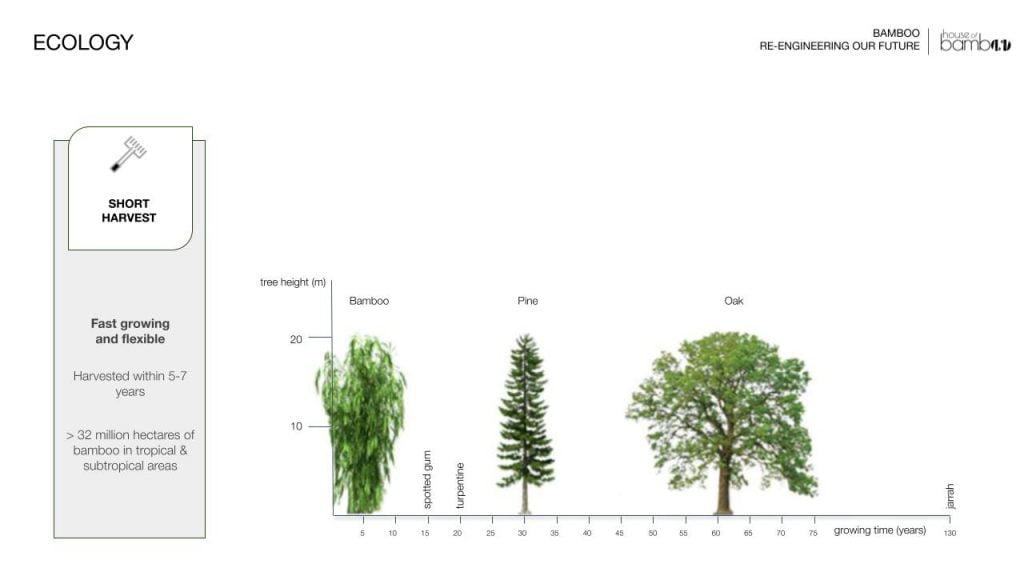

Bamboo is not a wood, but rather a grass that is indigenous to many parts of Asia. Bamboo is a sustainable resource that is typically harvested from managed forests with FSC Certification. Bamboo is an amazing plant that can grow faster than any other woody species.

But bamboo is not just a plant, it’s an entire ecosystem! Bamboo can grow up to twice as fast as wood and has been shown time after time that the fastest ecosystems in our world today come from Asia–where there are over 120 bamboo species found on this continent. Not only does bamboo provide us with precious resources for construction purposes it also helps stabilise soil erosion by holding onto nutrients which would otherwise be spread throughout nature’s systems when they’re removed through windrows (a technique used extensively during harvest). It takes just five years for this hardy grass to mature and produce new shoots, making it one of the fastest growing plants in existence. The harvesting process doesn’t damage either plants because farmers use managed forests instead – ensuring healthy environments while still producing enough material for everyone who needs building

The ancient art of bamboo harvesting has been practiced for centuries, but it is only recently that people have started paying attention to these natural resources. Bamboo grows in different sizes and colors with each species having their own unique trait offerings depending on what you want from them.

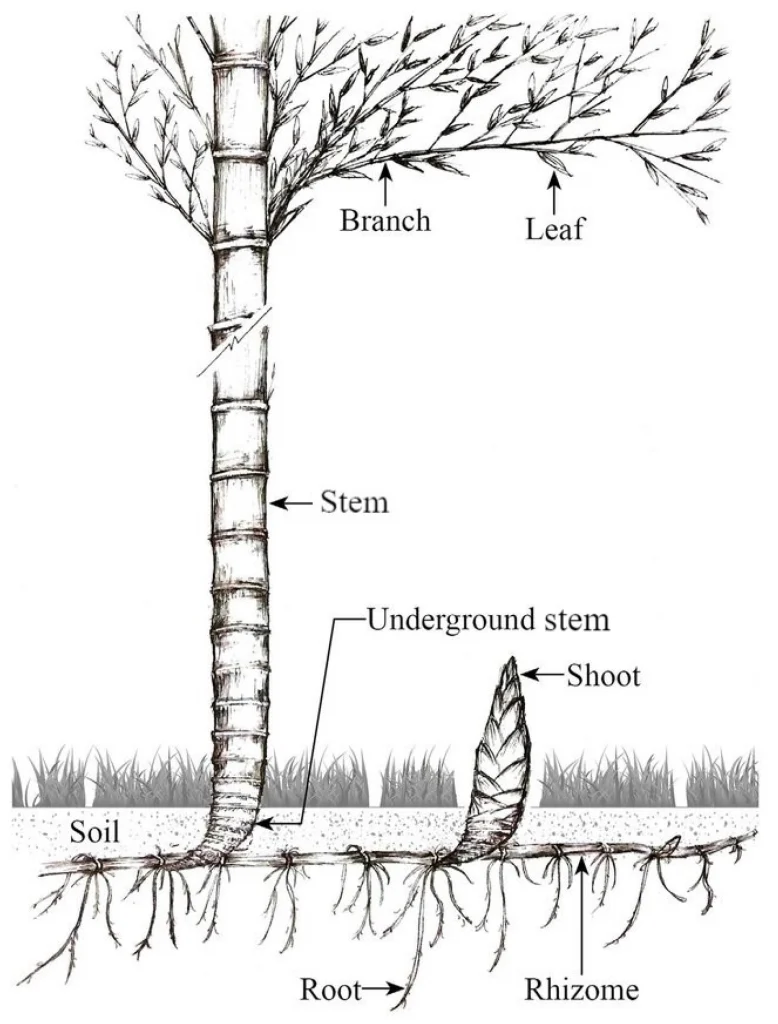

Bamboo, like sugarcane has fibrous roots which grow half to one meter below the surface. These are attached to the rhizome which runs underground horizontally with many growing points (shoots) or eyes similar to potatoes or ginger.

Each bamboo trunk takes 5 years to mature, with the rhizome producing new shoots each spring. These shoots reach their full height in approximately 1 year but their cellulose structure and therefore their strength increases each subsequent year. After 7 years, the cellulose structure starts to deteriorate, so the best time to harvest for construction purposes is between 5 and 7 years.

During it’s 5 year growth cycle bamboo requires very little maintenance. It does not require pesticides or artificial fertilisers to grow, it cools down the surrounding air by up to 8 degrees in summer and clumping bamboo purifies the air up to 30% more effectively than any other plant [Bamboo Down Under] https://www.bamboodownunder.com.au/20-fun-facts-about-bamboo

Bamboo trunks are often marked during their first year of growth, to make harvesting of aged plants easier. During harvest approximately 20% of a plantation is removed, with individual bamboo trunks cut just above the first or second node with a machete or saw. Cutting above the node ensures rainwater cannot collect in the trunk, reducing the risk or rot which could weaken the bamboo plant system. This is a labour intensive process as each individual plant must be identified as being of the right age to be harvested. “Unlike commercial forestry where trees have to be cut down and replanted, in bamboo plantations only mature stems are selected for harvest while younger steps are left untouched to further mature and develop.” [Guadua Bamboo] https://www.guaduabamboo.com/blog/bamboo-provides-and-endless-supply-of-timber

It is important to understand that one generation lives off what another leaves behind. More than a billion people depend on the bamboo plant for construction, cloth or food. Bamboo provides an environmentally friendly alternative due to how fast bamboo forests grow when harvested in a systematic fashion.

Bamboo releases 30% more oxygen into the atmosphere than hardwood forests of equivalent sizes and absorbs more carbon dioxide compared to other plants. It is a crucial element in the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

So back to decking…

Lets only talk about timber and bamboo as anything with a plastic composite is not an eco-friendly sustainable alternative, in my opinion.

Logging of merbau causes deforestation of rainforests as everything in site is razed to the ground. There is no question about that. In comparison, harvesting of bamboo forests is a more manual, labour intensive process which only removes mature stems. That’s got to be a plus.

Turning merbau lumber into decking requires a sawmill where a motorised saw is used to cut logs lengthwise. These lengths are then kiln dried to decrease green lumber moisture to ‘workable’ levels. Green lumber can twist, crack, warp and shrink in its physical size, so this process must be carefully controlled. Once dried, the timber is shaped and moulded before being packaged and shipped.

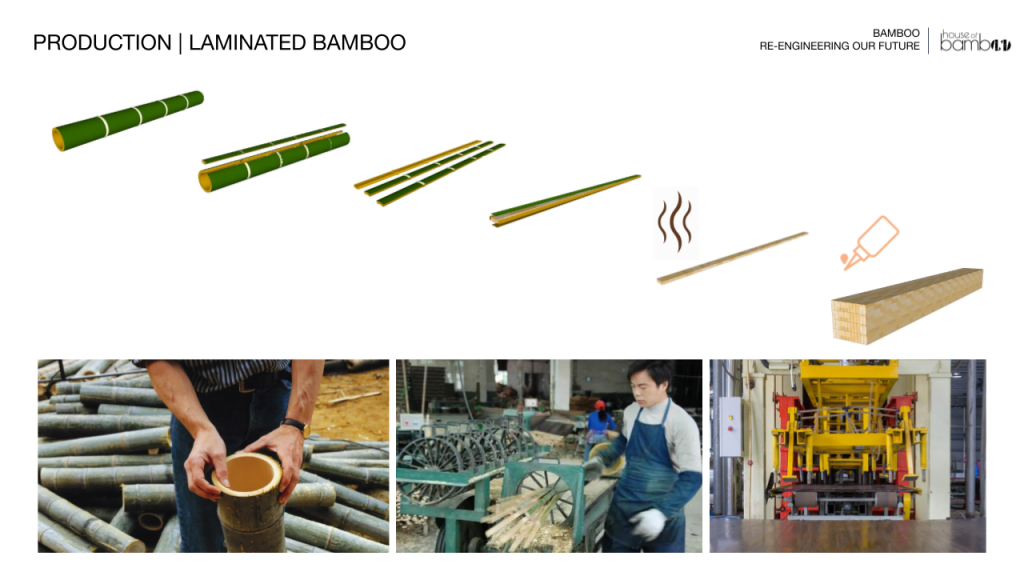

Turning bamboo poles into decking. Bamboo poles are transported to mills where the pole is ‘cored’ and cut (similar to an apple). These slats are carbonised to reduce X and then dried in a kiln before being laminated with glue under high pressure, in a patented process.

Decking Perth https://deckingperth.com.au/pros-and-cons-of-decking-with-merbau-timber/ has a very good article on the pros and cons of Merbau Timber. A couple of interesting points are:

- merbau decking is supplied unoiled

- merbau has a high tannin or oil content, so it tends to bleed when wet which could stain surrounding elements

- the hidden cost of maintenance as your merbau deck may require staining on a 3-6 month basis forever

Compare that now to bamboo decking:

- environmentally friendly

- supplied sealed and oiled in a range of colours

- annual maintenance recommended

- less wastage as boards are consistent lengths

- end matched

I see bamboo decking as the new innovative answer in our mission to change the world. It is not comparable to hardwoods because it stands alone. It has no plastics and is made from a resource that does not deplete our natural environment nor does its harvest impact our biodiversity.

I do not see Bamboo as a competitor in the realm of decking. It is an alternate material that does not impede on our environment and offers a far more environmental solution.

Once the “real” benefit of bamboo is understood, not only from its environmental impact but also the total absence of plastics and its ability to assist with the circular economy, then a true comparison can be made. One wouldn’t compare an electric car with a horse drawn cart, although they both achieve the function of transportation.

I hope this has helped you to understand why I am so passionate about the use of bamboo as a material in the built environment. If you have any questions, please feel free to leave a comment below or contact me directly. I would be happy to help you further. Thank you for reading!

Jennifer Snyders

BScArch | CEO

Photo Credit: